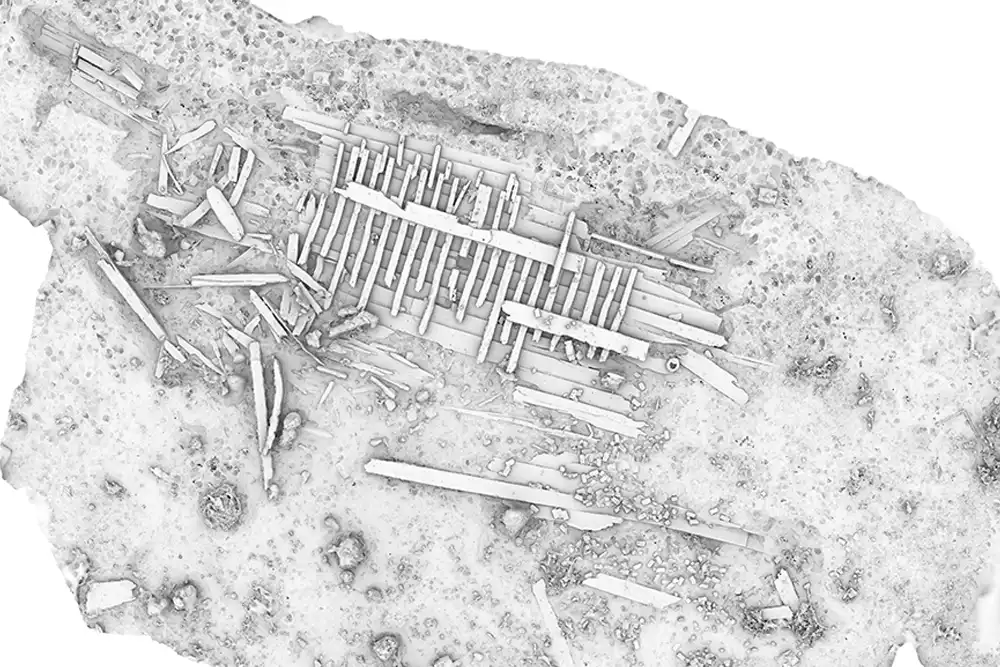

Maritime archaeologists from Denmark’s Viking Ship Museum have revealed the discovery of what they describe as the world’s largest ‘cog’, a medieval merchant vessel found during seabed investigations in Danish waters off Copenhagen.

The shipwreck was discovered in the Sound (Øresund), the strait between Denmark and Sweden, during archaeological surveys linked to the construction of Copenhagen’s new coastal district, Lynetteholm.

Buried beneath sand and silt for around 600 years, the vessel is the largest of its type ever identified, which the scientists say offers new insights into medieval shipbuilding and long-distance trade across Northern Europe.

‘The find is a milestone for maritime archaeology,’ said maritime archaeologist and excavation leader Otto Uldum of the Viking Ship Museum.

‘It is the largest cog we know of, and it gives us a unique opportunity to understand both the construction and life on board the biggest trading ships of the Middle Ages.’

A medieval ‘super ship’

The ship, named Svælget 2 after the channel where it was found, measures approximately 28 metres long, 9m wide and 6m in height, and would have had an estimated cargo capacity of around 300 tonnes.

Dendrochronological analysis – in which the tree rings from the vessel’s wooden planks are used to determine its age – dates the vessel to around 1410, an era when cogs formed the backbone of maritime trade across Northern Europe.

Large cogs were designed to be sailed by relatively small crews, and were built to make the hazardous voyage from the North Sea into the Baltic around Denmark’s most northerly port of Skagen.

According to the archaeologists, a ship of this Svælget 2’s size reflects a highly organised trading system within an extensive 15th-century trading network across Northern Europe.

‘A ship with such a large cargo capacity is part of a structured system where merchants knew there was a market for the goods they carried. Svælget 2 is a tangible example of how trade developed during the Middle Ages,’ said Uldum.

‘It is clear evidence that everyday goods were traded. Shipbuilders went as big as possible to transport bulky cargo – salt, timber, bricks or basic food items,’ he added.

Construction, preservation and rigging

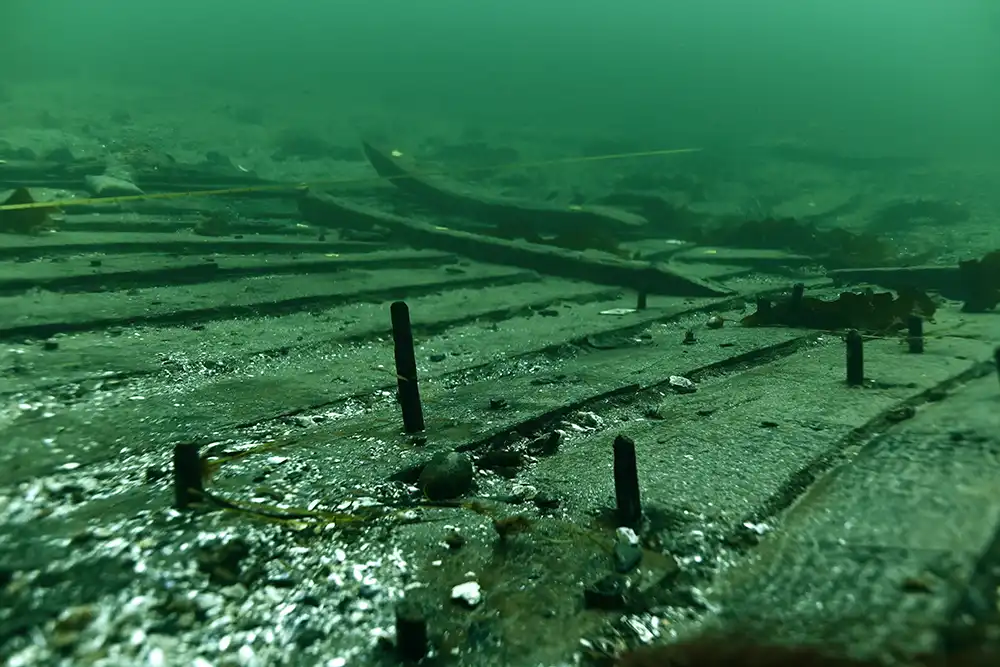

Analysis of the ship’s timbers shows that Svælget 2 was built using oak from two regions. The hull planking was made from timber sourced in Pomerania, in what is now Poland, while the frames came from the Netherlands, suggesting the ship was built in the Netherlands using imported planking alongside locally sourced structural timber.

‘It tells us that timber exports went from Pomerania to the Netherlands, and that the ship was built in the Netherlands where the expertise to construct these very large cogs was found,’ said Uldum.

The wreck was excavated at a depth of around 13 metres, where it had been protected by sand. The vessel’s starboard side from its keel to gunwale (the top of the hull) remains relatively intact, which has enabled the archaeologists to study construction details that are rarely preserved in other discoveries.

The researchers also uncovered extensive remains of the ship’s rigging, including a number of wooden deadeyes, through which ropes were passed to adjust the ship’s sails.

‘It is extraordinary to have so many parts of the rigging. We have never seen this before, and it gives us a real opportunity to say something entirely new about how cogs were equipped for sailing,’ Uldum said.

Life on board Svælget 2

Archaeologists also identified substantial remains of a timber-built stern castle, a raised structure frequently depicted in medieval illustrations but rarely preserved archaeologically.

The team also found the remains of a brick-built galley, thought to be the earliest example of its kind identified in Danish waters, and which contained bronze cooking pots, ceramic bowls, and the bones of fish and other sources of meat.

‘We have plenty of drawings of [stern] castles, but they have never been found because usually only the bottom of the ship survives. This time we have the archaeological proof,’ said Uldum.

‘We have never before seen a brick galley in a medieval ship find from Danish waters,’ he said. ‘It speaks of remarkable comfort and organisation on board. Now sailors could have hot meals similar to those on land, instead of the dried and cold food that previously dominated life at sea.’

Personal items recovered from the wreck include painted wooden dishes, shoes, combs and rosary beads, offering insight into daily life on board a large medieval merchant vessel.

‘The sailor brought his comb to keep his hair neat and his rosary to say his prayers. These personal objects show us that the crew brought everyday items with them. They transferred their life on land to life at sea,’ Uldum said.

Cargo and context

No trace of Svælget 2’s cargo has been found, which the archaeologists believe might be a result of the ship’s hold being uncovered when it sank, allowing goods such as barrels to float away on the tide.

Although its possible the hold may have been empty, the team has noted that an absence of ballast, which would have steadied an unladen ship, suggests that the cog was fully loaded when it sank.

‘We have not found any trace of the cargo. There is nothing among the many finds that cannot be explained as personal items or ship’s gear,’ said Uldum.

The Viking Ship Museum describes Svælget 2 as ‘a reflection of a society capable of financing, building and operating ships on an industrial scale.’

‘Perhaps the find does not change the story we already know about medieval trade,’ said Uldum, ‘but it does allow us to say that it was in ships like Svælget 2 that this trade was created. We now know, undeniably, that cogs could be this large.’

To learn more about the Viking Ship Museum’s work, follow the team on Facebook @Vikingeskibsmuseet, X @VikingShips and Instagram @vikingeskibsmuseet.

The post World’s largest medieval cog discovered off Copenhagen appeared first on DIVE Magazine.