Sperm whales are one of the largest creatures on the planet, and one of the most complex. Here are ten fascinating sperm whale facts exploring what we know so far

By Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) are the largest of the toothed cetaceans – and therefore the largest of all toothed predators – giving them a particularly unique standing in the global evolutionary chain.

Despite their massive size, like many other giant ocean creatures, we still know very little about these magnificent mammals. It is only recently that they have been afforded specific protections, in the form of Dominica’s dedicated sperm whale marine protected area, which was implemented in 2023.

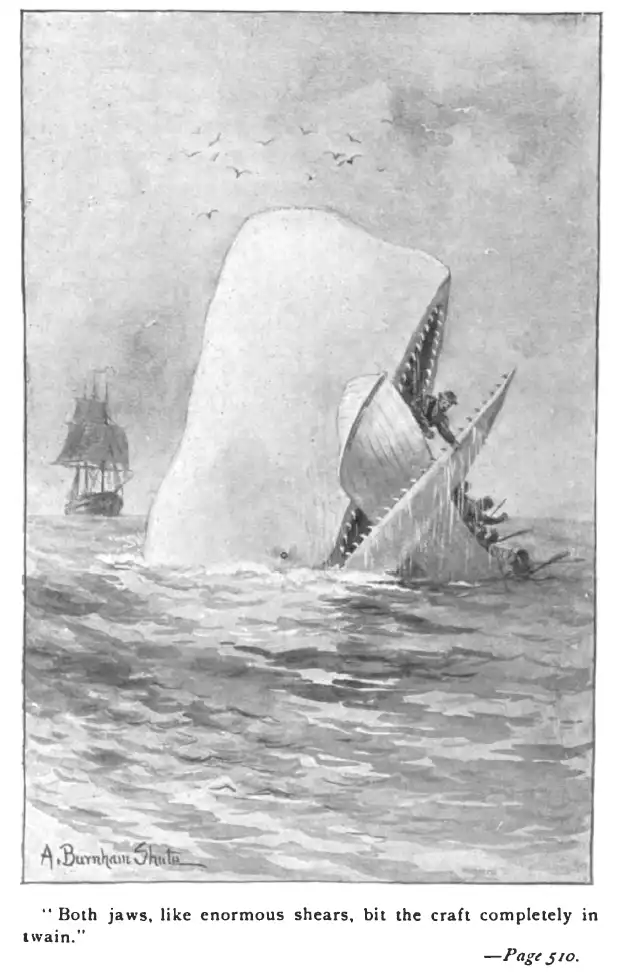

They are animals of myth and legend – sperm whales were the inspiration for Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, arguably the second most famous whale story in history, with only Jonah’s unfortunate biblical escapades (species undetermined) narrowly taking the edge.

Their unique characteristics and mysterious deep-sea lives make sperm whales the subjects of continued scientific interest, so let’s dive into the depths to uncover ten important facts about sperm whales that highlight their significance.

Gigantic giants

If any ocean creature has earned the term ‘leviathan’, then sperm whales are close to the top of the list. They are the largest of the toothed whales, and the third largest of all the whales – and, therefore, all animals on the planet – after blue whales and fin whales.

They are sexually dimorphic, with males averaging around 16 metres in length and weighing as much as 45 tonnes, and females averaging 11m (36 ft) in length and 17 tonnes in weight.

Even newborn calves dwarf many other species of cetacean, measuring 4 m (13ft) in length and tipping the scales at over a tonne when birthed – about half the size of a female when she first reaches sexual maturity.

The largest specimen ever recorded was an adult bull clocking in at 20.5 m (67ft), By way of comparison, blue whales can measure up to 30m (98ft) in length, and the largest fin whale ever recorded measured 27.5m (90ft).

Dive masters

Sperm whales are some of the deepest diving mammals, taking third place behind Cuvier’s beaked whales and southern elephant seals with a depth of 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) – at least, that we know about so far.

They are capable of holding their breath for up to two hours, where they patrol the depths in search of giant and colossal squid.

Sperm whales have only recently been seen feasting on their tentacled prey; prior to that, their diets were determined from the stomach contents of beached whales, and the scars of giant suckers around their heads – which have birthed titanic legends of their own.

Big heads, big brains.

If their bodies fall a little short (or, less lengthy, to be fair) of their baleen cousins, sperm whales have enormous heads, which can make up one-third of their total body length.

Within that sizable skull is the largest brain on the planet. At about 8000 cm3, or eight litres in volume, it’s about five times as large as a human’s and, at around 9kg in weight, around six times as heavy.

Big melons, big voices

The rest of the cavernous chamber that makes up a sperm whale’s head is taken up by cluster of organs filled with a huge volume – more than 1,800 litres – of a waxy fluid called spermaceti, from which the whale takes its name.

The spermaceti organ enables sperm whales to make powerful bursts of clicking sounds, known as codas, which they use for both communication, and echolocation to navigate and track their prey.

The volume of the clicks is immense, and enables sperm whales to talk to each other over thousands of miles.

The loudest sperm whale vocalisation ever recorded measured 236 decibels (dB) in the water – equivalent to around 170dB in the air – which is loud enough to burst the human eardrum.

By way of comparison, a firework exploding at a distance of 1m would measure around 150dB.

What was that name again?

Yes – all the classroom sniggering was true. Sperm whales are named after sperm (sperma ceti is Latin for whale sperm), because early scientists thought the gloopy substance inside the whale’s head was for reproduction, rather than chatting with their long-distance buddies.

They have also been known as ‘cachalot’, although the roots of this are uncertain. Some sources claim it came from an old French word for ‘big teeth’; others say the name of the whale with the world’s biggest head comes from an old Spanish or Portuguese word, cachola, which means ‘big head’.

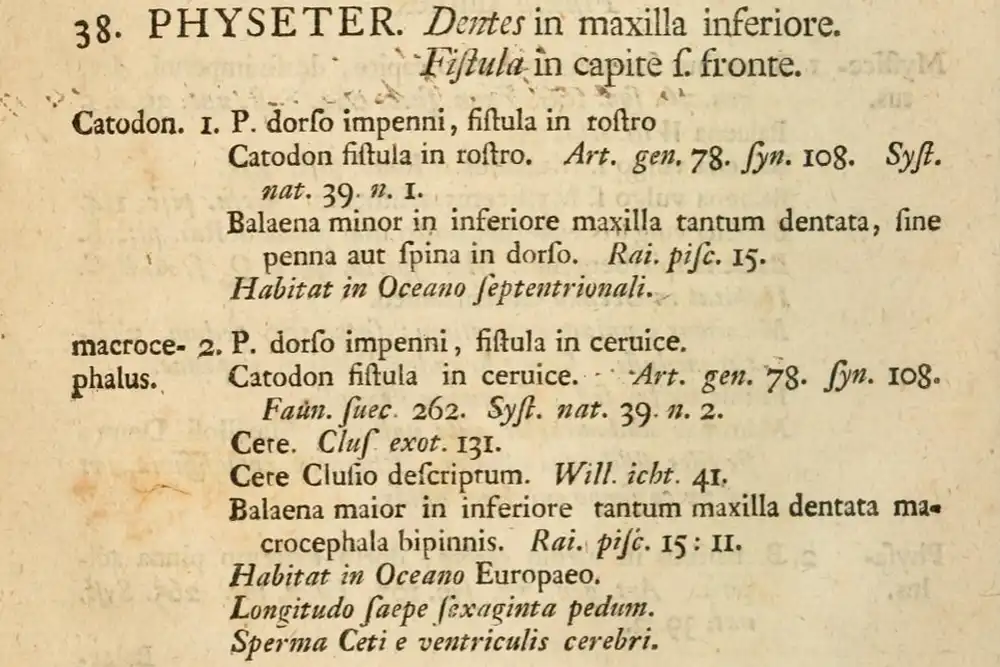

Sperm whales were first described in 1738 as Physeter catodon by Swedish naturalist Peter Artedi. Physeter from the ancient Greek word for ‘whale’s blow hole’, and catodon also derived from the ancient Greek meaning ‘down-tooth’.

They were later described in Carl Linnaeus’ 1758 Systema Naturae under both Physeter catodon and Physeter macrocephalos, derived from the ancient Greek for ‘big-headed’.

The accepted taxonomic name was P. catodon until 1974, when two Dutch scientists argued that P. macrocephalos was more correct. The name change was argued over for at least another 20 years, but as of 2025 – for now, at least – sperm whales are defined as ‘blow-holes with big heads’.

Mums and brothers

Sperm whales exhibit complex social structures, but are generally organised around a matriarchal family unit. In general, each group, or pod, contains an average of ten females and their offspring, led by one senior female.

Each pod belongs to a larger ‘clan’, which have been estimated to contain as many as 20,000 females.

Males leave – or are, perhaps, pushed out of – the group once they reach sexual maturity, but the females and their daughters stay together throughout their lives, and there are rarely any departures.

The bulls travel separately and do not appear to take part in the social grouping beyond seeking out a mate, when they will aggressively compete for female attention by ramming each other with their giant heads.

For reasons not yet understood, males will sometimes band together in groups, which appear to form a brotherly bond so strong that they will sometimes strand themselves – and die – together.

Talkative types

Complex social structures require effective communication, and it has recently been discovered that sperm whales have their own equivalent of an ethnolinguistic dialect.

The known clans of sperm whales so far studied have distinctive patterns to their individual codas, rather like humans in different countries have different languages.

In the same way that humans tend to gather with others who speak the same language, there does not appear to be any communication between clans, although whether or not this is because they don’t understand each other, or simply recognise that a particular communication is not meant for them, is not known.

Democratic decision makers

A study published in 2016 observed that sperm whales – which migrate over vast distances and often travel more than 50km in a single day – appear to make joint decisions about which direction they are travelling.

The study’s author observed that the whales would make gradual, but ‘messy’ changes in direction, before eventually deciding to make a decision and continue making their turn together.

The inference from the study was that the whales are contributing to a lengthy discussion about which way to go, before all deciding together.

While one should be careful of anthropomorphising animal behaviour, there are clear similarities to human committee meetings – it took the whales an average of 1.3 hours just to decide which way they were going.

Cetacean treasures

Sperm whale populations were severely depleted by whale hunting from the 18th to 20th centuries, but were more aggressively targeted than some other species for their unique traits.

The primary target of whalers was oil, extracted from blubber, which was used to make a wide range of commercial products, including oil for lighting and machinery, candles, soap and cosmetics – many things which have since been replaced by petrochemicals.

Sperm whales were also sought after for their spermaceti, which was used for similar applications, and ambergris, a waxy substance found uniquely in the digestive tracts of sperm whales, which was highly prized by the cosmetics industry for the manufacture of high-end perfume. As of 2025, ambergris is valued at around US$40,000 per kilogram, although trade is prohibited in America and Australia, and strictly controlled in countries where it remains legal.

On top of all this, the sperm whale’s huge teeth were a prized source of ivory, especially as scrimshaw, intricate carvings made by the sailors who captured the animals.

Current conservation status

Sperm whales have a widespread distribution, inhabiting both deep offshore waters and some coastal regions across all the world’s oceans from the Arctic to Antarctica.

Since commercial whale hunting was banned in 1972, the populations of many species have recovered, although all the ocean’s megafauna face threats from shipping and being caught as bycatch, especially by abandoned, lost and discarded ‘ghost’ fishing gear.

As a result, sperm whales are now classed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, rather than ‘Endangered’, although it is almost 20 years since the last assessment.

So much more to learn

Sperm whales, with their colossal size, intricate social structures and complex ‘languages’, are among the most intriguing of a highly intelligent family of marine vertebrates.

Research into whale vocalisations is finding increasingly deeper meaning to their sounds and recent discoveries put sperm whales close to the top of the list of animal communications that we may be able to understand and, perhaps one day, translate.

Dominica’s implementation of specific conservation measures is a step forward in ensuring the preservation of sperm whale populations, but there is much more work to be done to ensure they maintain their status at the pinnacle of cetacean evolution, and not fade, like Moby Dick, into myth and legend.

The post Ten fascinating facts about sperm whales appeared first on DIVE Magazine.