Physicist, oceanographer and author Helen Czerski talks to Jo Caird about Blue Machine, her award-winning book about the physics of our oceans

By Jo Caird

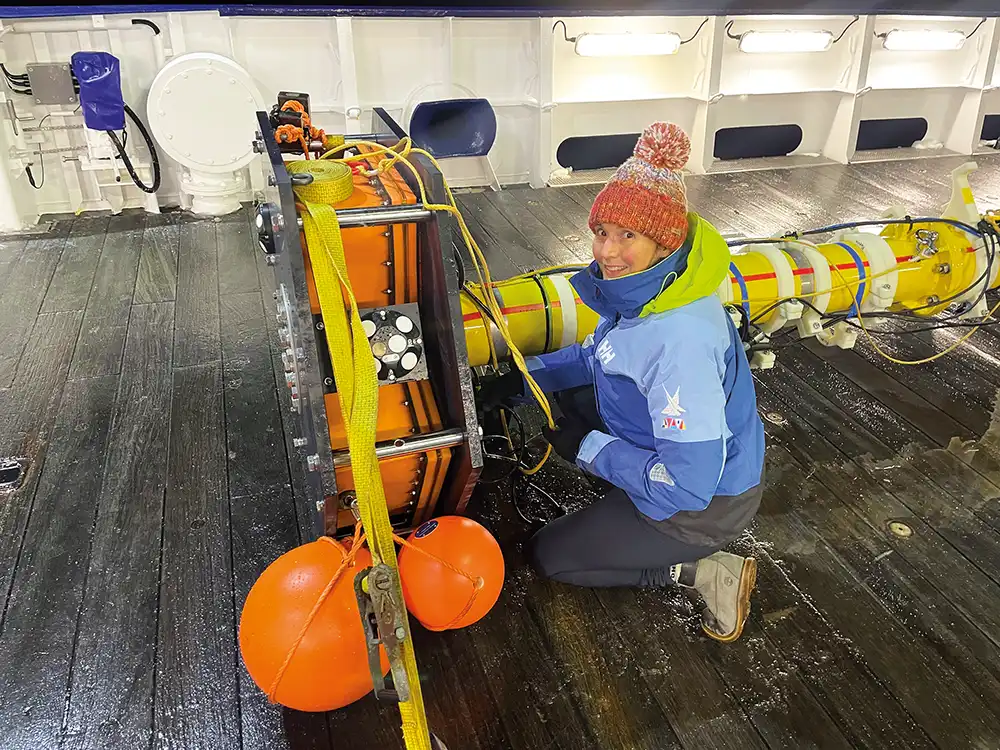

Helen Czerski had been working at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California for just a couple of weeks when she realised she needed to take up scuba diving.

Having completed a PhD in explosives science, but looking for a new field of study to suit her existing experimental skillset, the physicist had recently embarked upon an academic career in the science of bubbles.

‘I’d never thought about the ocean,’ Czerski recalls. ‘But it was very clear to me, once I’d had this light-bulb moment that the ocean was a place, that I had to learn to dive.’

Czerski progressed quickly, going from total beginner to dive master in less than three years, and training as a scientific diver from the start.

While she doesn’t dive in the course of her own research (bubble science is largely conducted underneath breaking waves in the open ocean, not a context that is particularly conducive to safe or enjoyable scuba diving), it’s an experience that has proved eye-opening in terms of Czerski’s attitude to the underwater world.

‘Diving is the closest any of us will ever come to flying,’ she says. ‘You get to explore a three-dimensional world. You look at things in a very different way and that is an enormous privilege.’

It was this perspective that informed the writing of Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes Our World, Czerski’s highly regarded popular science book about the physics of the ocean.

It covers complex topics such as how the ocean stores and redistributes energy, and the passage of sound and light through water, but in a highly engaging way – accessible even to those whose last grappling with physics was many moons ago.

Weaved in are many engaging stories of the ways that animals and people interact with the ocean, from the Scottish herring lassies of the early 20th century to the sharks of the frigid Arctic with a lifespan of more than 250 years.

Blue Machine is also beautifully written, making for a hugely evocative reading experience, particularly for those of us who feel at home in the watery realm.

Much to Czerski’s surprise, the book was recently awarded the 2024 Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing. ‘It was a shock, firstly, because I didn’t think I’d written a conservation book,’ she says with a laugh. But winning was an ‘enormous privilege. I see that prize as recognition that the ocean itself is interesting, one of the most interesting topics of our time.’

Tell us about writing Blue Machine.

I got a job at the Scripps Institution and soon realised that I’d never thought about the physics of the ocean. I totally got the idea that this was a liquid engine, and no one had ever told me about it, and that was really annoying.

I went on through my postdoctoral degree and getting a fellowship, and kept learning more about the ocean and I kept getting to the point where I could see that there was a story there, there’s this big thing that people aren’t seeing.

So when I was looking for an idea for my second book [her first, Storm in a Teacup: The Physics of Everyday Life, was published in 2017], this was kicking around in my mind. That someone needs to talk about the physics of the ocean, because no one’s doing it.

Also that I could see so many stories that were not being told because they didn’t have a place.

Has the response surprised you?

The first reaction tends to be, ‘I didn’t know the ocean did anything’. But as soon as people think about it, they get it. In retrospect, it’s very good timing: people are much more aware of everything that’s going wrong, but we’re past the point of conservation being about lists about reusable mugs and plastic straws.

The world is big and complicated, and people want to see the big picture. They want frameworks to understand the world that allow them to make decisions. And partly it’s just that people like hearing about worms with 1,000 anuses!

I’m very grateful for the response that it’s had. You write a science book and you expect that it’s going to get to a science-curious audience. This has gone so much further, and I didn’t expect that.

There are two novels that were out this year that have been long-listed for the Booker Prize, which cite Blue Machine as an influence! Suddenly, it feels like there’s a lot of responsibility, which is easier after you’ve written it than it is as you’re going along.

Did you feel a pressure to present solutions to the climate and biodiversity crises?

My role is not to suggest solutions, although there are some obvious ones. My role in this is to say, ‘Look at the world. This is what it is, and this is how it works. You take that perspective and you make your own decisions.’

There’s hundreds of books listing all the things you can do and should do and the world can do and should do. But the reason they are not ever going to work without at least some books like mine, is that they don’t make sense unless you’ve got a bigger perspective. And if you have a bigger perspective, you’ll work that out for yourself.

The thing that we’re missing is these frameworks on what it means to be a citizen of planet Earth, in a part of a physical system that works like this. Because we live by Earth’s rules – we’ve got to work with it and not against it. Other people can suggest solutions.

I’m not in that game, other than decarbonising and not destroying biology – those two things are very important. But just telling people doesn’t change their mind, showing them why it might matter, that changes minds.

What I want to do is show people the physical world as it is, and to show how interconnected is and beautiful it is, and then people will take that and do things.

What has diving given you, as an oceanographer?

A healthy fear of things looming! One of the most terrifying things that has happened to me underwater – and this won’t be unfamiliar to anyone who dives in the UK, I’m sure – is diving HMCS Yukon, which is a big warship that was sunk off the coast of San Diego in really turbid water.

You went down the rope and couldn’t see anything. You’d wait at the bottom and then there’s a moment where the soup clears and suddenly there’s this huge, great big battleship.

I hated that moment, it was just awful. But it was a very interesting reminder that we are visual creatures, and the ocean is not a visual place.

Obviously, if I had been a dolphin, I would have known that thing was there all along, because there would have been socking great audio reflection off it. But I was relying on senses that just aren’t very useful underwater, certainly in coastal areas where you’ve got very turbid water.

It’s a reinforcement that you are not evolved for this environment. None of the ocean creatures would have experienced what I did. I was out of my place.

Diving also gives me a visceral understanding of movement, because you feel surge, you feel currents pulling you along. That feeling of the ocean as moving and doing things, and that this is not just a passive pond.

And then just the privilege of seeing a different world. An octopus is the closest any of us are ever going to come to seeing alien life.

It amazes me that people go on and on about a possible chemical signature of something that possibly might be related to life on some exoplanet – it’s like, ‘There’s an octopus! Have you seen an octopus hunting?’

Entirely independently evolved intelligence, evolved for a different world, for a different set of physical constraints. Why would you not want to go and visit an alien planet?

When you’re put in the ocean, you see not only that your point of view doesn’t matter at all, but that there are so many different ways of solving these physical problems.

You see how the world looks if you just shift the rules differently. Experiencing that is a wonderful thing.

What will divers in particular get out of reading your book?

The thing about humans diving is that we only get to dabble around the edges. So even if you’ve had the privilege of seeing some of this underwater life, and you know what a living sponge looks like, seeing how that connects to the global picture is still something you’ve got to do in your imagination, really, more than in person.

But I think what you can do in person is imagine the connection. Once you know what to look for, you can see the connection.

For example, on remote islands in the middle of big oceans, sharks are often quite important in fertilising the reef, because they feed out at sea, and then they come into the reef to rest and to breed, and shark poo is fertiliser.

So then when you see a shark in that environment, it’s not just something which is exciting because it’s a big animal, you’re actually seeing the connection.

For divers, reading my book will hopefully change the way they see the world they already think they know. You can imagine the connections with the outside world.

Rather than just being a creature that goes past, it’s a part of a bigger, physical engine. You’re seeing the tip of the iceberg, but then hopefully you’ll have some of the tools to imagine the things it’s connected to.

The post ‘Machine learning’ – an interview with Blue Machine author Helen Czerski appeared first on DIVE Magazine.